I tried to get my buddy Brendan Leonard to write about this, but now that he’s being routinely quoted in the New York Times, he’s too busy.

It’s not easy being an engineer (or being married to one, as Francie will attest). You find yourself wondering about things that most other people aren’t wondering about. And, you have a different knowledge base to assess things that most people. Since we often take long road trips in Wally, I have lots of miles to wonder about things I see. One of those things is signs warning of ice on bridges.

I have not traveled as far down this rabbithole as a skilled practitioner like Brendan Leonard would, but it was, to me at least, an interesting journey. As a civil engineer, I have more than a passing knowledge of road and highway design and standards. While not a traffic engineer, I spent most of my engineering career working alongside them. In the U.S., the signage ‘bible’ is the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, or MUTCD as it’s referred to.

But first, why do drivers need to be warned about ice on bridges? It turns out, often ice can form on bridge decks where the road is still free of ice, which could surprise drivers to bad effect. One website said that ice formation on bridges was due to two reasons. First, it indicated that freezing wind strikes the bridge from top and bottom, giving it no way to trap heat. Secondly it asserted that bridges are typically built of steel and concrete, both of which are good conductors of heat, while asphalt is a poor conductor of heat. Which goes to show that you shouldn’t believe everything you read on the internet without some fact-checking. A quick search showed a range of conductivity for asphalt of 0.8 – 2.0 W/mK, and 0.5 – 2.5 W/mK for concrete, clearly debunking at least the second reason. It seems more likely related to the road surface being on the ground, which gives it a larger thermal mass and keeps it warmer for longer than a bridge deck.

Be that as it may, bridge decks have been demonstrated to freeze while the roadway on either side of the bridge is ice-free. Now the engineer in me thinks that, based on Newton’s First Law, this shouldn’t really be a problem if drivers don’t panic, at least for short, straight bridges. If it’s a curved bridge, okay, that could be a problem when you roll onto the ice and you lose the opposing force of friction to your centripetal force due to the curvature. I have also noticed that the definition of ‘bridge’, as least as far as placing bridge ice signs, doesn’t appear to be exact. I have seen them on the approaches to what I would term ‘culverts’, where there are still 5+ feet of ground over the top of the culvert and the road surface. That is going to behave just like the road surface on either side of it.

There turn out to be a number of variations of warning signs for bridge ice. Some of the many options are:

- BRIDGE FREEZES BEFORE ROAD SURFACE

- BRIDGE MAY ICE IN COLD WEATHER

- BRIDGE ICES BEFORE ROAD

- WATCH FOR ICE ON BRIDGE

- BRIDGE MAY ICE IN WINTER

- BRIDGE MAY BE ICY

- ICE ON BRIDGE

- WATCH FOR ICE

- ICE MAY EXIST

- BRIDGE ICES

- ICE

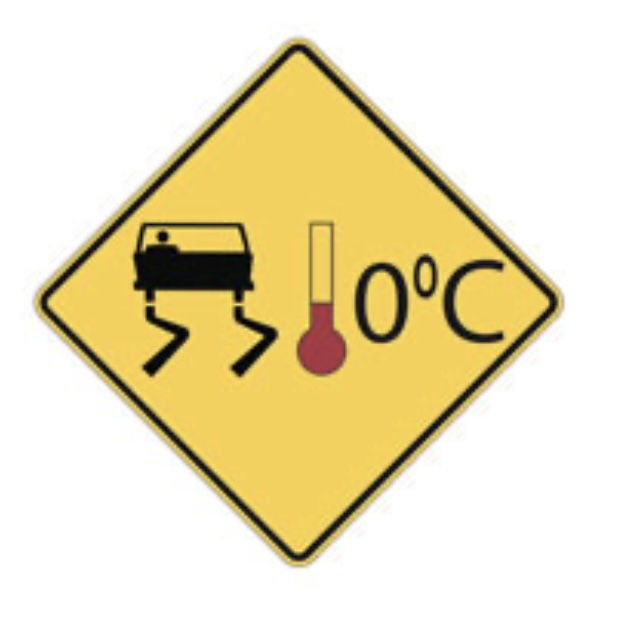

Since I’m always looking for the most efficient way to do something, I’m naturally struck by using six words to describe something when one word can suffice. I’m of course drawn to the simple ICE, although to be fair, this is meant to be installed under the MUTCD ‘slippery car’ (officially the W8-5 ‘slippery when wet’) symbol sign, giving an explanation as to why the road (or bridge) ahead might be slippery. Still, even the three-word options seem clear to me. There are some subtle differences. WATCH FOR ICE puts the responsibility on the driver. The BRIDGE MAY ICE IN WINTER implies that there’s only cold conditions in winter, which may or may not be true depending on locale. The more generic BRIDGE MAY ICE IN COLD WEATHER recognizes that cold weather can occur outside of the season normally considered as ‘winter’. BRIDGE FREEZES BEFORE ROAD SURFACE doesn’t give any hint as to when this might happen, but warns that, even though the road surface is not icy, the bridge might still be icy.

In Europe they favor graphics, having many different languages in close proximity. For warning signs, they utilize the red rimmed triangle. In the case of winter type conditions, they use the ice/snowflake in the middle of the red triangle, with the word ICE beneath it. In UK and Canada, they like the WC-30 slippery when wet sign, backed up with a BRIDGE ICES or ICY BRIDGE DECK placard below it.

It’s interesting to note that the U.S. ‘slippery when wet’ graphic shows a car, with a single driver (wearing a seat belt), level on the road, with a trail of tracks containing a slight swiggle. It could also be taken to mean that the guy just burned rubber, if looking at it with no other context. The Euro version of ‘slippery when wet’ graphic shows a car, balancing on two wheels, no driver (presumably ejected from the vehicle?), and tracks that appear to indicate it has completely flipped at least once (since the tracks appear to cross each other). Now THAT gets your attention!

You may think this is just something that poor engineers and their long-suffering wives have to deal with, but there are real-life consequences here. The previous Texas standard was W8-13T, WATCH FOR ICE ON BRIDGE. These signs were made with a seam in the middle, so in summer they could be flipped down, and would read either “Don’t Mess with Texas” or “Drive Friendly”. This required staff to flip signs depending on the season or weather, which given the number of ‘bridges’ in Texas, is a non-trivial exercise for Public Works staff.

On a cold January morning, Calvin Kitchen died when driving his pickup across an icy bridge, as he swerved and was hit head-on by another vehicle. For the three days leading up to the day of the accident, the WATCH FOR ICE ON BRIDGE sign was open, complete with flashing lights. On the day before the accident, based on a NWS forecast that showed warmer and drier weather the next day, the sign was folded and the lights shut off. When the following day, the day of the accident, dawned still cold, staff was displaced to redeploy the WATCH FOR ICE ON BRIDGE sign, but by the time they arrived, Mr. Kitchen had already met his demise. In 1993, the Texas Supreme Court reversed a decision that had held on appeal, and said that Calvin Kitchen’s family would make no recovery from the State Department of Highways. Some time later, the MUTCD standard, and the Texas standard changed to: BRIDGE MAY ICE IN COLD WEATHER, creating a sign that doesn’t require maintenance, and just reminds drivers that in certain conditions, the bridge may be icy.

So what are the lessons for us? Well for one, if the temperature is near freezing, watch out for bridges, especially if they’re curved. And of course, use your common sense and check stuff you read on the internet.

And finally, let’s not work ourselves up too much about danger everywhere… the icy bridge signs are there every day, but there’s only a few days a year that they actually point to a real danger. So let’s not make the world a scarier place than it needs to be, and get out there and LIVE.

Great fun to read, but I admit I tripped over one sentence. When you said “ You may think this is just something that poor engineers and their long-suffering wives have to deal with…” it seems like you are assuming that all engineers have wives… a surprising assumption for an engineer to make I would think! Perhaps you meant “ You may think this is just something that poor engineers and their long-suffering partners have to deal with…” Or it could just be you and Francie!

Love to you both, -Jeff

You’re right, could have been partners… or even just people who have engineers in their family or friend group for that matter…